It’s no secret that we all need money to live. This is true even for religious and spiritual leaders as well as their students. That’s why, in this episode of The Missing Conversation, Robert explores Buddhism within the lens of money and monetary attachment. Buddhist teachers rarely deal with the importance, and excessive emphasis on money or how attached their students and society are to it. One of the ways they often miss an opportunity is by detaching themselves from communication and by not carefully addressing what it means from the original Buddhist teachings to be balanced.

It’s no secret that we all need money to live. This is true even for religious and spiritual leaders as well as their students. That’s why, in this episode of The Missing Conversation, Robert explores Buddhism within the lens of money and monetary attachment. Buddhist teachers rarely deal with the importance, and excessive emphasis on money or how attached their students and society are to it. One of the ways they often miss an opportunity is by detaching themselves from communication and by not carefully addressing what it means from the original Buddhist teachings to be balanced.

Buddha himself did not outright denounce money and material possessions. He simply cautioned against letting such worldly things control, change, and possess us. When greed and hungry desire become us, we lose sight of how we could use these material riches to help the world and humanity at large. That’s when resources like money become evil and destructive.

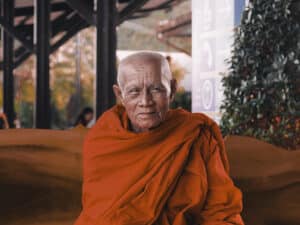

Buddhist monks, teachers, and followers are encouraged to reduce or, indeed, remove their connections to materialistic things in our world. This is especially true for money. Buddhist teachers often act as if they want to appear as being detached from money and similar worldly, material needs. They implicitly depict themselves as being one step more ‘removed’ from and mostly in control of these human needs. But there’s a question to be asked — how much of this detachment is voluntary and internal? How much of it is to avoid facing rejection or ostracization from your community?

Like other humans, including you and me, Buddhist teachers also depend on money to survive and share their teachings with their disciples. So there’s an opportunity here for Buddhist leaders to share their understanding and values about detaching from money and simply reframing their thinking of money as an essential tool for life. Something that is necessary for survival in balance and moderation.

As followers and students, we need to ask our teachers to explore the topic of money and our collective attachment through the lens of their teachings. Similarly, if teachers took some time to share how they manage their own relationships with money, it might help us all model it in our lives. This would help us focus on a balanced relationship to money itself and help us reduce our attachment to it over time, allowing us to see money as a tool for balance and generosity.

Mentioned in this episode

The Global Bridge Foundation

Note: Below, you’ll find timecodes for specific sections of the podcast. To get the most value out of the podcast, I encourage you to listen to the complete episode. However, there are times when you want to skip ahead or repeat a particular section. By clicking on the timecode, you’ll be able to jump to that specific section of the podcast

Transcript

Announcer: (00:04)

The Missing Conversation, Episode 35.

Robert Strock: (00:08)

It’s very, very evident that attachment to money is the very most socially accepted addiction.

Announcer: (00:21)

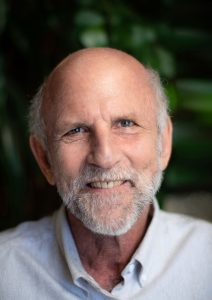

On this podcast, we will propose critical new strategies to address world issues, including homelessness, immigration, amongst several others, and making a connection to how our individual psychology contributes and can help transform the dangers that we face. We will break from traditional thinking, as we look at our challenges from a freer and more independent point of view. Your host Robert Strock has had 45 years of experience as a psychotherapist, author, and humanitarian, and has developed a unique approach to communication, contemplation and inquiry born from working on his own challenges,

Robert Strock: (00:59)

A very warm welcome again to The Missing Conversation where we do our very best to address the most pressing issues that the world’s facing today and where we look for the most practical, inspiring programs and innovative ideas to support a greater chance of survival for our plant today, we’re going to stay focused on, which is the best way for religions and spirituality and their traditions to benefit by facing and presenting human challenges and sides of themselves on the parts of teachers to represent both the essential part of life, the spiritual part of life, and also the human part of life. However, today we’re going to turn the page and look specifically at the Buddhist teachers and students and the issues of both transparency and dealing with the perhaps greatest attachment we face in our Western world today, which is the attachment to money and how the Buddhist community in general has not given this enough attention that from my vantage point, the world very much needs us to do. We’ll take a briefer look at the group that we’ve also been covering that has been deemed spiritual, but doesn’t particularly have a set of spiritual beliefs or traditions, but they just live in integrity with caring with heart, but they don’t really have a belief structure other than their internal sense of living a sincere, authentic and caring life. Like to start off with introducing Dave, my partner at the Global Bridge Foundation and dearest friend for ages.

Dave: (03:14)

Thank you. And as always, I appreciate being here, um, in particular connecting the values and the, and the, and the Buddhist, and I think probably even broader as you’ll discuss, uh, the way they, the way they move through the world, without regard to looking at the issues around money and things like that.

Robert Strock: (03:40)

Right, right, right. Thank you. And the things like that are really going to be transparency as well. So, I believe strongly that through the last 40 plus years of really being in a lot of different segments of the Buddhist communities that both Buddhist teachers and students really need to deal with what the Western world’s greatest blind spot is, is the attachment to money and wealth. And the benefit that could happen if the teachers and the students insisted on that as being part of the general teaching retreats seminars, guided meditations, meditations. And we’re also going to focus on the importance of transparency as we have in the prior episodes. And finally, we’ll continue to take a look at this group of people that we’ve identified as spiritual, even though their beliefs would not make you or them believe that they’re spiritual, but they’re just naturally generous, soulful, honest with integrity.

Robert Strock: (05:12)

So, this issue of starting with wealth and money is also there for the, what might be called integrity, caring group without beliefs, but not as much as the students or the teachers in the Buddhist community. There’s a little bit more of a tendency for the naturally generous core group that doesn’t have beliefs to be what I would say a teeny bit more generous in my experience, although it’s also quite evident that they, like most of us in the Western world, would do well to question for the rest of our lives. Am I in balance given we’re in 2021, given that we’re facing all these planetary dangers? And how much benefit could be caused if we all were questioners. One of the ways that I have really started this conversation with students and teachers in the Buddhist community is do you think Buddha’s teachings on money and how he would be if he were here from the best that we know, do you think that simulates the way it’s being presented today?

Dave: (06:46)

As you say that what comes to me is just the story of Buddha himself. And I think that’s an important reflection on exactly what you’re, what you’re getting at. And I wonder if you could include that or mention that as, as, as it relates to this question, you ask?

Robert Strock: (07:05)

Yeah. That’s just where I’m going. Exactly. So, Buddha himself really portrayed that money is not evil no more than any other resource. Money only becomes evil or destructive if it starts to change us and possess us, it becomes destructive. If it starts to control our thoughts and actions, and he really emphasized how greed causes money to become destructive. And that balance itself is the key. He really emphasized really what he called the middle way, that there’s a sense of sharing and a balance with being self-sufficient. And he would have likely had unbelievable amounts to say if he was here about our world in balance and how central this dominating emphasis on success and money and wealth is really one of the greatest sources of robbing our world from peace, generosity, and helping others.

Robert Strock: (08:37)

And how important it is that this motivation of being focused on money as being unconsciously, for most people, in the center of our lives. And obviously I’m only talking about people who are ones that have it well, we’ll address the people that don’t, as well. But it being so much in the center of our lives is a form of operating of the spirit. It’s a form of harm to the people that don’t have it. And this is where we, as students, can ask more from our teachers and teachings and applications, by the example of our personal teachers and our inner lives to apply what the Buddha has so brilliantly expressed in so many different ways about balance and how money can be used simply as a tool to live an essential life. Now, what you’re going to hear in this end, and in future episodes, are a continuous series of stories of my interactions.

Robert Strock: (10:00)

In some cases over the last 50 years in the Buddhist situation, it’s more like 45. And one of them was a man I had a wonderful conversation with that was in Northern California. And he was sharing how he really loved the work that he was doing, but he really didn’t like having to live in a different neighborhood. And that he was in a community where the students had a congregation and it was Buddhist. And he wasn’t part of a main center in Northern California of Spirit Rock, but he was sort of an independent that did some work there did, but had his own congregation. So I asked him, I said, well, well, why wouldn’t you bring that up as part of your Dharma talk or part of your teaching? And he went, well, to be honest, it’s a little scary. Some of the people are pretty spoiled and, and, uh, are really potentially needing me to just lead the way by being an example of somebody that is living a very frugal life to model for them.

Robert Strock: (11:22)

And if I demand too much of them, I have some concerns that some of them might leave. Now, he said that in a very humble way, he wasn’t, uh, let’s say proud of it. So, I persevered and said, do you think it might make sense, and do you think, do you think if Buddha were here he would be encouraging you to be having this be maybe a very central part of your teachings. And he was one of the few teachers that actually took in that message. And from that time on, we continued to be developing a, let’s say colleague relationship. He actually brought it in the teachings, the Dharma talks and changed some of the ways that people donated, as just voluntary, to having clear, suggested donations and having a tie into the wealth that they had and how important it was to be in balance and to be a questioner.

Robert Strock: (12:32)

So that was one of the good news. One of the success stories was another one where one of my dearest friends who really introduced me to probably three quarters of the Buddhist community over a period of 20 years of teachers had a teacher that was really revered by the teachers who, who came to this one of the great centers in the California area. And she came up to me and said, gee, I have a great idea. I want you to support me with it. Now that we were on a silent retreat at the time we weren’t supposed to talk, but we were breaking the rules. And I said, you know, I think that’s a terrible idea. And her idea was, let’s go down, down in the morning when we’re having this meeting that is designed for donors of the center. And I’m going to make the suggestion that all the Buddhist teachers that are the prominent ones that are connected to the two major centers, write letters to their followers and ask them to donate to the central teacher.

Robert Strock: (13:45)

So, he can be freed forever and would allow him to just focus on the work. So, I had the conversation with her the night before and said, you owe it to the teachers to ask them if they want in before you volunteer their offerings, because they’re all relying just to a large extent on their following for their own survival. And if they’re in, I think that’d be great. But if you don’t have their buy-in first, and you’re only presenting it to about 10 teachers in this meeting the next day, then aren’t you going to possibly leave them in a feeling of guilt or anger or feelings of inadequacy if they don’t come through. And she said, oh, you know, she was, she was upset with me. And that led to a little bit of a falling out. The next day, went to the meeting, and she brought up the idea and I raised my hand and said to the teacher, aren’t you at all concerned about the fact that these teachers might be responding from guilt or pressure or feeling like they had to be loyal, rather than really have conversations with each of them and make sure that it was not coming from an outside source, it was coming from inside them.

Robert Strock: (15:12)

And his response was no, I’m not concerned, not concerned at all. Well, to me, that was a real sign of a blind spot of my relationship to money is way more important than their relationship to money. And maybe not way more important, but it just felt like it was an insensitivity. The areas so rarely even talked about between the teachers and basically that went out. And I guess I would say from my end, unfortunately it didn’t manifest that much because I believe the teachers really weren’t given the buy-in.

Dave: (15:53)

Having been there for that conversation with him and experienced other, other times as well, I wonder what your take was about him personally, and why he bought in?

Robert Strock: (16:11)

I think he truly believed that he was at a level that was more developed and advanced than the other teachers and that in a certain way, he had a depth understanding that warranted him to be taken care of for life, with money, and that the teachers would take care of themselves. Now having talked to so many teachers and seen how they hadn’t taken care of themselves again and again and again, which we’ll get into in this episode and maybe the one that follows, I knew that they were prone to guilt. I knew they were prone to feeling pressure, not to ask the community for money, not to be seen as caring about money. That that was part of the deal. That was part of the respect. That was part of the honoring that my teacher is someone that’s not materialistic, perhaps like me, and that allows me to have more respect for them.

Robert Strock: (17:17)

So, I believe it was just that sense of having an entitlement of being one step more developed. And therefore, I think it’s fine if I get taken care of for life and look at all the good that I can do. And of course I didn’t really disagree. I actually did agree that he was one step more developed. It’s just that the consideration around money and talking about it openly. And are you feeling pressured? Are you okay with where you are? Do you have challenges around it. That whole area isn’t being talked about? So that was my objection.

Dave: (17:55)

And I just want to say another, another take as, and this is a, a distant many, many years retrospective take about just the trust and life that lacked in that moment, the, the feeling of, uh, a teacher in that position, uh, saying sure, when at the same time professing to say trust in life, you know, you, you, you are, you are, or I’m going to help you be okay, wherever you are with money, without money, whatever. And that was not reflected in that decision, in my view, in my view.

Robert Strock: (18:37)

Yeah. I completely agree with you. And of course, I know how he rationalized that. Well, all of us, this is just part of the natural manifestation. I didn’t even bring it up. Life is providing, so it’s a very subtle thing and obviously open to interpretation. So, another situation happened where sort of a very surprising short story. My stepson actually was on the verge of writing a book and was interviewing mostly Buddhist teachers, but teachers from a variety of traditions. And one of the very, very most well-known teachers that I had a couple of friends that were connected to him and arranged for him to be able to talk to them. And he said, you know, what’s your relationship to money? Because I know that you’re in a tough situation, he was facing some serious physical challenges that were enduring. And his response was in such a beautiful, innocent way.

Robert Strock: (19:48)

He said, well, I feel like if I ask people for money, that would be yucky. It was such a startling word that he used because it was so unsophisticated and innocent and childlike. And then he went on to say, I feel like if I ask somebody for money, and then they came to visit me, I’d just be seeing dollar signs, rather than their soul. I wouldn’t be able to really get out of the way with not seeing them as maybe being a source of future revenue, or maybe they’re thinking that while I gave to you, and I’m entitled to more permission or more, uh, ability to see you and learn from you. And he just couldn’t get it straight. Now that to me was a reflection of many, many decades of not dealing with money, as just another part of life, health, money, friendship, community, just another spoke of the wheel that is so important, especially to be connected to the world.

Robert Strock: (21:00)

And I would say, especially now in 2021, that the issue has become even more dramatic. Now, as we look at this again, reflecting on the community, that is what we’ve been calling the integrity, caring community that doesn’t have beliefs. As I mentioned in the introduction, this slightly less of a tendency to see money as yucky. And it’s usually a bit more a part of their actions because they’re naturally caring and there’s a bit more of a tendency to be generous. But like most of us in the Western world, they were taught, well, it’s good to have security and it’s good to take care of your family. And it’s good to make sure that you have enough for a rainy day. So, I would say there’s a 20% improvement in that general community. And it’s important that we keep tracking what’s the difference in a variety of so-called spiritual communities.

Robert Strock: (22:07)

And I asked for the forgiveness on the part of any of you that don’t identify yourself as spiritual in any traditional way. But if you look at your actions and your attitudes, you would realize that they’re really the same as what the Buddha or Jesus or the core major teachers have professed of loving your brother and sister, as if they’re yourself. Now, one of the things that’s pretty evident is that Buddhist teachers themselves can really pull it off being ambitious because part of the tradition is that the students expect them to be nonmaterialistic. It’s a tradition that’s been going on for 3,000 years. And it’s hard to know how much of that is a current vow of moderation or even slightly below moderation, or if it’s natural or being driven by the fear of rejection or concern about being seen as needing money, just like a normal person.

Robert Strock: (23:26)

So, it’s very evident that minuscule attention has been given to this attachment and all the retreats that I’ve been in, the hundreds of tapes of teachers that I’ve received immense benefit from and all kinds of too many ways to even begin to acknowledge. But yet the absence of this is like an enormous elephant, maybe two elephants in the room. So, one of the questions that I would ask you is, do you have the courage if you’re oriented toward Buddhism? And for that matter, really outside this episode, any tradition to ask your teacher to direct more attention in the area of money and attachment to money, and maybe even to include their own relationship to money, to help you model that. And can you see how, because of the way we’re raised, and if you look at the amount of people, not only the Buddhist tradition, but then it saved $2 million, $3 million, $5 million and way more than that, and the thousands and tens of thousands of people and the trillions and trillions of dollars that are just in savings investments that have nothing to do with caring for the world.

Robert Strock: (24:58)

Can you see how crucial and connected this is to the well-being of the world and the various likelihood of survival of the world and the contribution to global warming and how different it would be? Not only if we were raised that way, but if we raised ourselves that way, it’s very, very evident that attachment to money is the very most socially accepted addiction. And I’m using the word addiction to try to draw attention to us where it’s perfectly okay. If you want to have a lot of money, maybe not in the eyes of people that don’t have any money, but all the halves are pretty much wanting to have more. And that line keeps moving. So it’s, it’s very, very unpopular, which I’ve run straight into in my conversations through the decades to really attempt to challenge that socially accepted addiction. So, in closing for this episode, I think it’s very important to make the connection to how not dealing with money and the teachers not dealing with money and the students not dealing with money.

Robert Strock: (26:31)

And the Buddhist tradition is itself unwittingly contributing to the natural disasters that we’re seeing on such a regular basis, like global warming and terrorism. Terrorism might be a little bit more subtle, but if you realize that terrorism goes to the poorest areas of the world, you can see how holding onto money is creating the perfect fertile grounds for terrorism and the more obvious areas of class imbalance nationalism. And by definition, these groups have their motivation toward being identified with their wealth, identified with it as safety and security, and maybe even wisdom, but certainly sensibility. And this, in my eyes, for all of our survival potential and our kids and our grandkids needs to be re-evaluated. And we as parents and grandparents and enlightened teens, we all need to really ask our teachers and ourselves and our Buddhist teachers as we’re emphasizing in this episode to have it be central so that we can integrate it as a healthy part of our lives.

Robert Strock: (28:10)

And not as something like, well, our spirituality is over here and our money is over there because from my vantage point, money is just energy and it’s dynamic energy if we have a lot of it. So, the importance of this being central is so key. And so, I would ask you, as we’re ending, to ask yourself the question, what is your relationship to money? Is it really imbalanced? Do you really have a sense of what’s enough? And can you see that if you bring this into your Buddhist tradition and maybe be a catalyst, a major catalyst, whether you’re a student or a teacher that you will be practicing the core tenants of what Buddhism and the Buddha really brought to the world. So, I thank you very much for asking that question hopefully for the rest of your life. And I appreciate your attention. Thanks very much.

Join The Conversation

Join The Conversation

If The Missing Conversation sounds like a podcast that would be inspiring to you and touches key elements of your heart, please click subscribe and begin listening to our show. If you love the podcast, the best way to help spread the word is to rate and review the show. This helps other listeners, like you, find this podcast. We’re deeply grateful you’re here and that we have found each other. Our wish is that this is just the beginning.

We invite you to learn more about The Global Bridge Foundation—an organization collaborating to heal communities and the world at TheGlobalBridge.org.

Visit our podcast archive page