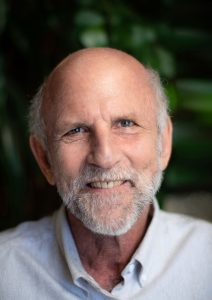

This week, Robert is joined by a special guest and his step-son Brent Kassel. They meet with a sense of purpose and shared vulnerability here on The Missing Conversation. Brent is the co-founder and CEO of Abacus. Abacus is a holistic wealth management company that invests over 4 billion in companies and projects that, above all, do not create harm in our world. A significant portion of the funds aim to help society and the environment directly while earning competitive investment returns. He is also the author of The Next Fifty Years of the Racial Wealth Gap, and What You Can Do About It, as well as, It’s Not About the Money, which was named one of the top five business books of the year by Kiplinger.

This week, Robert is joined by a special guest and his step-son Brent Kassel. They meet with a sense of purpose and shared vulnerability here on The Missing Conversation. Brent is the co-founder and CEO of Abacus. Abacus is a holistic wealth management company that invests over 4 billion in companies and projects that, above all, do not create harm in our world. A significant portion of the funds aim to help society and the environment directly while earning competitive investment returns. He is also the author of The Next Fifty Years of the Racial Wealth Gap, and What You Can Do About It, as well as, It’s Not About the Money, which was named one of the top five business books of the year by Kiplinger.

Being faced with his own mortality after a surprise health event, Brent began to ponder, how much was enough? Engaging his wife and children he began a deep financial exercise to quantify this. Working with outside experts, including Robert, he began to work out ways to use the surplus to have as much impact on reducing suffering as a family could. Although Brent has dedicated himself to a life of giving, Robert and Brent candidly talk about the fears and complicated feelings around making these non-traditional financial and life decisions. As well as what’s involved in contemplating and recalibrating what it means to have a good quality of life both for oneself and the greater world.

Philanthropy as well as a healthy life balance is directional. It is not about waking up tomorrow and being that perfect ideal version of yourself that you wish you were. It is not about radical change and doing it all in one month. It is about ongoing contemplation and directionally guiding yourself with this new kind of habit or muscle that you are developing. This episode encourages us to ask, “What is needed to optimize your most fulfilling quality of life?” This includes your relationship to money and the present state of the country and world.

Mentioned in this episode

Abacus Wealth Partners

GiveWell

LIFT

The Global Bridge Foundation

Note: Below, you’ll find timecodes for specific sections of the podcast. To get the most value out of the podcast, I encourage you to listen to the complete episode. However, there are times when you want to skip ahead or repeat a particular section. By clicking on the timecode, you’ll be able to jump to that specific section of the podcast

Transcript

Announcer: (00:00)

The Missing Conversation, Episode 54.

Brent Kessel: (00:04)

I don’t think the world is at risk. And the reason I say it that way is cuz the planet’s gonna be fine. I think the human species could make itself extinct.

Announcer: (00:18)

On this podcast, we will propose critical new strategies to address world issues, including homelessness, immigration, amongst several others, and making a connection to how our individual psychology contributes and can help transform the dangers that we face. We will break from traditional thinking, as we look at our challenges from a freer and more independent point of view. Your host, Robert Strock, has had 45 years of experience as a psychotherapist, author, and humanitarian and has developed a unique approach to communication, contemplation and inquiry. Born from working on his own challenges.

Robert Strock: (00:56)

Like to give you a very warm welcome again to The Missing Conversation where we address or do our best to address the most pressing issues that the world’s facing today and where we look for the most practical, inspiring programs, innovative ideas, and individuals to support survival on our planet and finding a sense of unity, inspiration, and fulfillment that both we and the world needs so badly today, we have a very special guest, a very unusual one in, in my life that exemplifies someone who has lived a life that I would say really expresses so much of the essence of a psycho-political life in his relationship to the world and has a very interesting background and has made personal and global choices throughout his life when he had other great options that lead me to feel very honored to have him on our show today, as far as I know, he’s still in process, as he’s relatively young. In fact, I’m very proud to say that he’s been my stepson for 35 years and has remained my close, close friend and colleague, since that time, I’m also happy to say that his mom and I share a unique love as well. And it’s part of The Missing Conversation to stay close to your exes, if at all possible. And for you that have listened, you probably understand the importance of maximizing our connection to everyone, especially those that have been your dearest. So, I’d like to first start off by introducing Brent Kessel. Hi Brent.

Brent Kessel: (02:57)

Hi Rob.

Robert Strock: (02:58)

So, Brent is the co-founder and CEO of Abacus, a holistic wealth management company that invests over 4 billion in companies and projects that aim to help society and the environment while earning competitive investment returns. He’s also the author of two financial plans, The Next 50 Years of the Racial Wealth Gap and what you can do about it, as well as it’s not about the money, which was named one of the top five business books of the year by Kiplingers. Brent is highly active in philanthropy and impact investing presently serving on the national board of Lift Communities, which breaks the cycle of poverty by building families well-being, financial strength, and social connections to lift two generations at once. So, Brenty what are you currently working on that you’re most inspired about?

Brent Kessel: (04:07)

Thanks, Rob. Um, it is great to actually hear you read that bio and just feel my gratitude for how big a role you’ve played in all of those things. Uh, I’ve known you since I was 19 years old, uh, Rob called me young, which is kind of him, but I’m 53, so I don’t feel that young anymore. So, what I’m working on, that I’m most inspired about at the moment is something I’m playfully calling “The Enough Project.” And that is it started, for myself, a couple years ago when I had a health event that really kind of grounded me in my own mortality in a very poignant and surprising way. And that led to me having some conversations with my wife and our kids about how much is enough for us enough consumption, enough security, and what do we want to do with the surplus that we’re privileged enough to have beyond that enough point, which is such a privilege, uh, in a world where, you know, many, many, many, many people–the majority–do not have any surplus or even enough.

Brent Kessel: (05:25)

So yeah, The Enough Project for me started with a lot of kind of journaling and reflection on what are the voices in me that resist this, that like really still want pleasure at a, at a higher level than I’ve had it, or really want more security, that could never be too much security, um, and kind of grappling, you know, writing down everything they have to say and engaging them, um, along with this other voice that was emerging saying, huh, gonna die , and not that you know, long from now, even if it’s decades from now, it’s still not that long. Um, and so it really then led to a pretty deep financial planning exercise to quantify how much is enough and start working with outside experts around ways to use the surplus, to have as much impact on reducing suffering as we, as a family, could.

Robert Strock: (06:24)

Uh, as you know, well, we’ve had a multi-decade conversation about a version of how much is enough, something I’ve called economic satiation point, and working with clients and friends. It’s kind of mind blowing, living in the year 2021, for those of us that have enough to not be in this questioning. And I, I feel like what you said was really crucial regarding death, that we really do believe seemingly that we’re gonna live forever and live most of us live our lives as if we are, um. I had a client recently that said, well, until I met you, I thought I was gonna live forever. And I think that that’s so crucial for those that are in the position where they clearly have, or maybe semi clearly have enough and they’re interested enough to ask that question. So, I’m so grateful to have you in my life, you know, part of the family and part of the extended family, and you being such a inspirational leader in your own right, to spread that word, as we’ve talked about many times without trying to induce guilt. But really, when it’s coming from that sweet spot, it’s not even being generous. You know, it’s, it’s, it’s really just getting to be fulfilled and experience a joy that I’d be hard pressed to call anything else as joyous. How about you?

Brent Kessel: (08:21)

Yeah, I, well, I’m, I do remember, you know, even your original writings about economic satiation point, I think, I think it was like 1991 was the first time I remember seeing your paper on that, you know, and at the time I was very young and, and like, it was just in my mind, it was like a number. And when I get to that number, I’ll be free and you know, one of the realizations is, oh, wow, there’s no such thing, it’s not binary. Um, it’s actually just, it’s a choice. It’s like a yoga pose, you know that, oh, I just choose to breathe a little more fully into this part of my body right now. Um, and it doesn’t, yeah, it doesn’t magically change everything. And so, I think for me, there are moments where it feels joyous, where I feel, like, so as a result of The Enough Project last year, 2020, we were much more philanthropically, focused, and gave a much higher number and percentage of our resources to philanthropy than we ever had before by several orders of magnitude.

Brent Kessel: (09:31)

And that was joyous. Like, I really, you know, there were some voices saying, wow, well, what if this, and what if that, and you might get to the end of this year and think you were an idiot for doing this in the middle of a pandemic. Um, but I had none of that. So that was a joyous experience. And then there are other times when, when I’m feeling uncomfortable, you know, when I’m that, that voice is there, like saying, well, wait, wait, wait, wait, are you sure? You know, is this really quality of life, or are you just trying to, you know, please the impact investment community, or please Rob, or please the inner part of yourself that doesn’t want to be viewed as a greedy white guy. You know, and in those moments, it’s very hard to access the joy, but I, I do keep hearing your voice in my head saying aim for that, aim for a quality of life, not kind of an external standard.

Robert Strock: (10:26)

Yeah. I mean, the way that you’re expressing the other voices and the internal conflicts and the, uh, crucial honesty of being at, let’s say three levels: One is you have enough and so what, which is not you. And then there’s, I think there’s a level where you have enough and it really does require a continuous questioning of, am I doing this for other people? Am I doing this outta guilt? Would this really be fun? Will this be joyous? Will I really feel connected or will I still feel empty or those kinds of questions. And I’d like to briefly summarize psycho-politics, just so those that are listening, who have not heard it before will have a real good sense of it. It’s very simple to understand, not, not maybe as easy to practice. And the first of three principles is it’s natural, of course, to care for your family, to care for yourself and to view that as sacred.

Robert Strock: (11:35)

But when we look at 2021, and we see that, that means we might be taking care of, emotionally, 5, 8, 10 people, 15 people in your case, maybe 20, cuz you, you extend far out into, into your family system. You realize that if all the wealthy people in the world do that, that means maybe 98 or 99 or 99 point some percent of the wealth is being saved for the family system and the energy that’s being put out, staying with the first principle, the energy that’s being put out, is so compartmentalized that we have maybe 500 million compartments on the planet and nobody’s substantially taking care of the earth. Nobody’s substantially taking care of poverty. Um, so the first principle is the psychological element. And the second principle is really how are you dealing with either money if you have it, or if you don’t have it, how are you dealing with having dignity about going for survival and realizing that you have even a, maybe a tougher job.

Robert Strock: (12:47)

I won’t even say maybe you have a tougher job to not get angry and mad at people that have wealth and really provide for your family. Really give it the best efforts, really having self-esteem based on your direct totality. So that would be the second phase of maximizing your relationship to money in 2021 and having a perspective of it in the world. And then the third principle, which is what you demonstrated already spontaneously is questioning for the rest of our lives. Am I, how much am I imbalanced in relationship to money and time and energy of having a favoritism toward my family, toward my friends and a world that’s in global warming, a world that’s in vast economic injustice. So many areas that we, we can barely, uh, talk about them. We can’t really even mention them all, in our country. And so the principle of recognizing 2021 and that this is not a false alarm. This is, this is a real thing that our planet is in danger of dying and, and the, the poor are in desperate need of opportunities to care for themselves and are underestimated in their capacity to, to do what so many of us have tried to do or part partially doing. Uh, but this idea of the family system being so sacred, and the planet, and the poor being so second grade to us challenging that question and being in that questioning, which obviously, like I said, you’ve displayed beautifully. So what, what’s your sense of that?

Brent Kessel: (14:41)

Yeah, I appreciate you saying I’m displaying it beautifully. It, it doesn’t feel so beautiful often. It feels messy. Um, and yeah, I’d say that the principle that I’m struggling with in myself right now of psycho-politics is my tendency to make, you know, my difficult feeling states, which for me is, is mostly fear and anxiety. Um, like other people’s responsibility or the, the external world’s responsibility. Like I need people I work with to do this differently or change that. And then I can focus more of my energy on the poor, on the planet, um, or I need them to come along or I need them to approve of me as I do this or that. Um, and so I think that’s, that’s one of the biggest shifts that I’m, I’m in the midst of, which is, uh, you know, I call it FOPO fear of other people’s opinions.

Brent Kessel: (15:46)

Um, so it’s kind of like FOMO, but, um, you know, and if I’m just getting better at, um, at allowing other people to, to not, you know, to disagree with something really strenuously or not like, you know, the, the way I’m, values I’m expressing, um, cuz I am, I’m in a lot of communities. It’s not, you know, I’m not really a solo guy. Um, and um, and so things I do and things I say generally have an effect on others and sometimes it’s not the effect they want, you know, and, and I do wanna come clean and say like, I certainly still favor my family over, you know, poor people. Like I could take the money I spend on giving my two sons, you know, very first rate educations and, you know, help many thousands of African or South Asian kids, you know, get over sanitation related illnesses or I could dig, you know, I don’t know how many wells, but probably 10 wells a year, you know, for people who don’t have fresh water.

Brent Kessel: (16:50)

So, you know, I, I think that’s one of the places where I’m trying to not look away from that. I’m trying to ask the courageous questions around. I just wanna make that explicit to myself rather than just implicit. Like it’s explicit that I’m choosing to spend, call it, you know, a hundred thousand dollars between the two on a college education, um, when I could be doing all these other things. And, but I’m not choosing to spend a chunk of money on something luxurious, uh, you know, extra luxurious or a, another sort of leveling up of our lifestyle. And with that, I do want to be highly effective in our philanthropy.

Robert Strock: (17:38)

I, I so appreciate your honesty. And, and I, I think that that’s something that we all have to emulate. I think it’s an easier task by far to do it at 72 than it is at a younger age and really wanna put out a strong message to everyone listening, please don’t compare yourself. Please don’t compare yourself with Brent or with me, or it’s a matter of how much do you give, et cetera. It’s like every little dime, no matter where you are matters so much. And the whole idea is like having an arrow, moving in a direction to move toward caring about people that are disempowered and caring about the planet and at some level not so much because you should, but because there’s, there’s a sense of your, our own survival really is threatened for the first time in history on a global level, not maybe you could say the nuclear war with the Soviet Union, but this is something that is so much more predictably trending and potentially irreversible. But the idea is not to feel guilty because you favor family.

Brent Kessel: (18:54)

I just wanna jump in Robbie because I, I actually, I frame that a little differently. I’m I don’t think the world, uh, is at risk. And, and the reason I say it that way is cuz the planet’s gonna be fine. I think that human species could make itself extinct, but I actually don’t even think that will happen. I think what’s much, what’s most likely is that, you know, the 80% of humanity that just is living hand-to-mouth, you know, subsistence farmers, um, even, even, you know, people in the United States in the plains, you know, states are living, living in, you know, urban settings, uh, you know, that are having brownouts because of excessive power surges and things like that. I think we have a lot of climate refugees that is gonna be a huge, huge issue. I think we have tremendous biodiversity loss where we’re literally just not gonna be able to cure certain diseases that we would’ve been able to cure.

Brent Kessel: (19:56)

Had we not put however many hundreds or thousands of species into extinction, that we’re currently doing, but to me it’s like this beautiful blue marble floating in space is gonna be fine. It’s gonna keep floating in space until the sun explodes us. Um, most of the species in the plants and nature, it’s kind of like when you go to a place, you know, that’s been abandoned by humans even for five years, like nature just does its to magic and takes it back over. And so, you know, I think it’s, it’s kind of our hubris to assume that our own extinction equals the world’s extinction. And secondly, you know, you and I are gonna be fine. We’re gonna be able to move to cooler climates. We’re gonna be able to buy the more and more expensive food because of crop failures. We’re gonna be able to get clean water, but so many billions are not. And you know that, I know, I know, you know, all this and that, that’s where we’re pointing our attention, that the urgency is that, you know, we could have major social unrest and, and like cultural collapses of systems if we don’t take care of each other.

Robert Strock: (21:04)

Yeah. I, I hope you’re right. Uh, and I really meant to emphasize humanity, not so much the globe. So, I stand happily corrected, uh, and even, even taking, or it’s not even even taking what you’re saying as the truth that a large percentage of people that are living in, uh, insecurity are the most threatened by far. And I, I believe I happen to be more concerned that it it’s gonna be wider spread, but it, it doesn’t matter in a way, in a way in the sense that if it’s all the people that are food insecure, all the people that are in drought areas, all the people that are gonna be, uh, in fire areas, it is so vast that we have a chance for purpose that is right in front of us. And whether that’s taking care of your family really well with a great attitude, cuz you realize that’s your purpose of life, cuz that’s the most you can do cuz you’re raised in a certain country and that’s your potential and God bless you for giving it your all or whether it’s, you’re in the middle and you have a little bit of spare time and you give a little bit of spare time or you have a few dimes or you have a lot of dimes.

Robert Strock: (22:23)

It’s not a measurement of how much you give. It’s a matter of how much your totality, effort, and intention you open up into that. There’s this big world that, that we wanna maximize our potential. And that, that purpose, you know, going to the therapeutic side of me for 50 years is like that sense of purpose of maximizing your potential. No matter where you are, is really, uh, the key to a certain kind of mental or spiritual or planetary health.

Brent Kessel: (22:58)

Absolutely. It’s, I love what you’re saying and it, it reminds me that we’re so much better at, in community than we are on our own. Um, you know, there’s that African proverb, if you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go farther, go together, um, Lift Communities, which you mentioned in my bio is this amazing poverty intervention. And one of the keys to how successful they are is that they, they do these group coaching sessions where you have 5 or 7 or 10, uh, parents, uh, who have children eight or younger who are either homeless or in extreme poverty. And yes, they’re getting coaching from an expert person and yes, they’re getting some direct cash payments, but one of the biggest things is, is creating this social fabric and accountability and seeing that they’re not alone and that everyone has these feelings of having failed their, their kids or failing their own expectations for themselves.

Brent Kessel: (23:59)

So, yeah, and I, I love what you’re saying about every dime matters and it really, really does. Like when you, when you look at some of the issues that are being so underfunded in the world, you know, so deeply neglected. Um, I mean we, in the work I do in Sierra Leone and Ghana, you know, which is the sixth poorest, Sierra Leone is the sixth poorest and, and most hunger impacted country out of 200 countries or whatever we have. Um, you know, you, we can increase someone’s income, you know, by, God, by five X, um, with a really small investment, you know, with, with like $50 a month of, of, you know, them sharing and, and getting some education around how to do crop rotation, how to do no-till agriculture, how to, um, use better seeds and inputs so that they can actually feed their families and maybe have a little surplus to sell that they can then pay for some healthcare and some education.

Brent Kessel: (25:03)

Um, so there are tremendous resources out there for folks, you know, even if you have 10 bucks or a hundred bucks or whatever, um, there’s people who’ve done the research on what the most neglected areas are. And honestly like most philanthropy is, is pretty wasteful, cuz a lot of people just give based on relationships. They have, you know, I’ll scratch your back, you scratch mine or whoever’s mailing them um, or inviting them to their fundraisers. Um, and by and large, those are not the most effective interventions. So, someone giving 20 bucks to something that’s, you know, one of the most neglected interventions can often be much more important than someone giving $20,000 to the average thing.

Robert Strock: (25:46)

So, if you were gonna really guide the listener to where, whether it’s directly to you, because you have the resourcefulness in whatever way that would happen or two or three organizations that you feel like are really using the dollar in the maximum way for energy benefit. Where would you guide them?

Brent Kessel: (26:12)

Yeah. I can give you a couple ideas right now, but maybe what we can do is we’ll put a few links in the show notes, uh, on, under the podcasts for your listeners to click on. But “Give Well,” is one where folks can go, and there are a number of Give Well Funds that focus on different areas, focus on climate, focus on poverty, um, and, and have done amazing research into what the most effective interventions are. One of the Give Well interventions is called “Give Directly,” which basically found that when you’re dealing with poverty, uh, giving cash directly to the poor is by far the most cost-effective way to help them work their way out of poverty. We’ve so often had this kind of colonialist western view that, you know, we know better and we’ll come in there with our, you know, Masters in Sociology or whatever and tell you how to educate and tell you how to do healthcare and we’ll make sure the money’s not being wasted and, and the cost, number one, the fact that we’re not trusting the local folks means we’re missing so much nuance and so much on the ground knowledge. Number two, um, we, we’re now paying this westerner probably a fairly hefty salary by local standards to be that kind of educator or, or kind of regulator, you know, to make sure the money’s not being wasted.

Brent Kessel: (27:41)

So Give Directly says, look, you’re, you’re way better off just taking that money and giving it and sure, some of it’s gonna get gambled away or spent on alcohol, but the lion’s share of it is gonna be directed to the most necessary resources and they know better than we do.

Robert Strock: (27:56)

I think it’s a great idea, uh, to put the link, so I’m gonna hold you responsibleto send it to our engineer, Mark, and have him include that at the end. And I just really wanna acknowledge you and, it’s truly like a goose pimpling joy to be part of raising someone and your own heart is moved. And then you see that that person that you’ve been raising is introducing you to a whole bunch of people that are expanding your potential and your world, and then meeting other people to expand their world and helping people find each other. And you’ve definitely been a catalyst for expanding the source of circles that we can overlap with each other. You know, I’m immensely grateful for having that happen in my life with you. And I think that it’s, it’s such a mirror in the biggest and smallest of ways that if you have a close friend and you are struggling for survival, being able to collaborate and like you’re talking about with, with Lyft or when you can just help each other, help others, or even if it’s helping your own family in the maximum way that the key is that arrow of direction of finding potential.

Robert Strock: (29:21)

That is your greatest potential and not in a perfectionistic way, but in a natural, organic way, that’s going to allow us to move forward. But I wanna come back before I end that little riff about the joy of interconnecting with us and you can’t ever expect somebody in your family, let alone a friend, to join you in a sense of purpose. And I’m truly grateful that that we’ve gotten to complete the circle of overlapping circles and being interconnected and hope that that feel is contagious for the listener that they can look at, oh, who would be the one or two or three people. I don’t think most people would be able to look in their family, but if they were more, more gratitude for them, but just being able to think that way, of how can I connect with another, where we can expand together, is such a joyous thought, In reality.

Brent Kessel: (30:27)

No, it really is and I’m, I’m very touched at your, you know, your goosebumps and your emotion that I can feel. And what I wanna say back, uh, also for the listener is it started with you, it started with you meeting me at 19, at that walk on Santa Monica beach and you reaching out into kind of my reality and at the time, my pretty intense suffering, and extending your unique gift to me and your vulnerability to me. And, and, you know, so I think if I was listening to you and, and didn’t have, you know, the, the background that you and I have shared, I might think, well, I’m not sure who that friend is or who that family member is that you know, is already obviously that person. And what I would say to a listener, who might find themselves thinking that is, who can you really reach out to and support or ask the question or share your own vulnerable edge of what you’re grappling with.

Brent Kessel: (31:32)

And maybe it’s even just, you know, some confusion and some kind of messiness around these questions. Like it’s not clear it’s, it’s not, it’s not clear for me at this point, even after knowing you Rob for 35 years and having grappled with them, it’s like, it’s, it’s uncomfortable questions at times. And I think, I think that open vulnerability, the way in which you reached to me with your vulnerability and you know, what you were grappling with at the time as a 37 year old man gave me so much permission to just be myself and with all of the parts that I thought were unattractive or un, you know, not strong and wouldn’t be able to make it in the world that well, um, you know, and so I think the resourcefulness that I brought into your life and the networking and the relationships is, is really just looking at what my, you know, comparative advantages or my kind of offering can be. So yeah, to your listeners, like every listener has their own unique gift that is, you know, special to the family or the friend group. And, uh, and then there’s probably one or two folks you can look at who really need that gift more than anyone. And, uh, and just offering it super vulnerably and openly, I think creates that the, that beautiful reciprocity that will hopefully ensue.

Robert Strock: (32:55)

Yeah. I, when you talk about the vulnerability, it’s like, I, I really do remember our very first walk, our very first meeting on the beach and the openness to be vulnerable in sort of the ultimate vulnerability is about our own shared mortality with human beings. But whenever we open that vulnerability, it becomes so evident that we could have been anyone. You know, that we could have been the homeless person, we could have been born in another country. I don’t think any of us are, uh, presumptuous enough or at least not too many of us to think that, oh yeah, I knew exactly–I decided I was gonna come here because I was, I was superior, and I think I’ll be in a wealthy family cuz of course I’m fantastic. You know, I don’t thinkanybody’s gonna be that pompous and so we have, and we had that shared vulnerability to, to realize that in a certain way, we have to say that we were lucky.

Robert Strock: (33:54)

Uh, I don’t think we preearned it, and I think the more that becomes clear, we stay vulnerable because a part of us wants to take care of ourselves and our family. And a part of us says, God, if we’re fortunate, how can we not want to share or, or as a transition should share, but the vulnerability is a real key. And that’s part of the questioning. You know, it’s like, in that third part of questioning for life, you know, how can I be in balance? What is my idea of balance? Forget me, forget Brent, forget everybody. You individually going into that question and asking what would optimize my life, what would make me feel like I’ve lived a life of fulfillment and joy and if that’s to be utterly self-centered, I know I have no influence on that. I know there’s no influence on that. You know, that, that everybody has to be true to themselves. But the idea of being a questioner and being vulnerable is something that, you know, I couldn’t possibly try to support–I’ll never be able to support it enough.

Brent Kessel: (34:59)

I could just add to that. I, I think it’s so crucial to ask that question. Um, the way I like to put it is like, what’s one small step I can take in that direction, which I know you said before, it’s directional. It’s not about, you know, tomorrow waking up as that perfect ideal person, version of yourself that you wish you were. Um, I I’ve taught money workshops for years, as I know, you know, but your listeners probably don’t know. And so much of our work at Abacus is about people’s relationships to money, whether they have wealth or whether they’re struggling and still just trying to, you know, get, get off the hamster wheel or, or, you know, build something that will create some mix of security and pleasure and generosity. Um, and, and it’s just incredible how deeply rooted our relationships to money are, how unconscious they are.

Brent Kessel: (35:53)

And I often equate it to the metaphor of being the captain of one of those giant containerships those big, big, super tankers that you see out on the ocean. And like, you know, if, if you turn the wheel of that thing, just one degree, and then you keep it turned for like six months, that super tanker ends up an entirely different hemisphere than where it started. So, it’s not about radical change and, you know, and doing it all in one month, it’s about directionality and holding on to this new kind of habit or muscle that you’re forming. Um, and it’s unreal the way, you know, I, I just have had so many clients through the years who turn around a couple years later, five years later, 10 years later, they’re like, oh my God, I had no idea that I could get here. Um, you know, and obviously we’ve all, not all, but many people have heard the sort of magic of compound interest or a lot of financial planning basics. So that’s the simplest version is, you know, save X percent and you’ll have this much, but the, the same thing is true of generosity. And the same thing is true of just, you know, having choosing to live a little more simply in your life and enjoying things that don’t cost a lot of money. There’s so many habits like that.

Robert Strock: (37:13)

I truly love the emphasis and I really hope this comes through maybe more than anything else of one small step at a time, and that everyone is capable of a next move. As a matter of fact, you’re not capable of a next move unless you die. And so everybody’s capable of that next move and it’s, it’s being moved enough to where you want to question that what’s my next move, and what would be balanced for me. And, if that was implanted, I often think of what if our world, if our parents in our early education were giving this kind of holistic education where it’s, what’s your next move to be fulfilled, and you’re gonna have a tendency, you’re gonna have a bias to have it be about you. And for some that might be perfect, but for others, it won’t be.

Robert Strock: (38:12)

So, what’s your next move to consider that we’re interconnected in some way that we can’t explain we’re all gonna die, we’re all gonna be, we’re all vulnerable, whether we recognize it or not. And what is our very next move? And maybe our next move we’re talking about this week, or maybe we’re talking about the next five seconds, but, but never to underestimate the value of a small change. Like you’re talking about, you know, with just moving one small degree with a big ship, um, or for that matter, a small body, just one, one small little move. The earth, I believe right now, there’s never been a time in history where we’ve been given a chance to find dignity, something that’s not a moral standard, but it’s something that comes from within that that feels like, gosh, maybe I would like to be more interconnected in some way.

Robert Strock: (39:15)

And like I say, we can’t measure one with the other, cuz for one it’s supporting the family and it’s looking for the next meal and for another it’s economic and for another it’s it’s volunteering. But it’s something that from my vantage point would do well to be part of mental health for those that are not dealing with very serious mental health issues. And it ties into psychology. You know, we’re gonna later have a Missing Conversation on psychology, which isn’t values neutral. You know, it is valued toward the interconnectedness of human beings and how central that is to mental health. And it is just a real, um, it’s a sweet spot that most of us we’re not raised into. So one of the things I, I wonder for you when, when you’re facing, because for me as 72, I think I’m gonna make it outta here before the worst of the worst happens, but you, and certainly your kids,

Robert Strock: (40:17)

and I know for me, my son, you, grandchildren, multiple grandchildren. And when I look at my extended family, you know, I really am deeply, uh, both concerned and inspired in a certain way, grateful that this is a time where an aliveness is like, um, it’s like you’re given a situation where you know, every little bit matters, but I’m wondering how you face the global warming, economic inequality, terrorism, corruption, and stay afloat and don’t sink. And I know it’s not black and white. I know there’s different levels, but what, what are your leading thoughts? What are your leading guidances for you as to, as to how you deal with those, uh, very real conditions that we’re facing on the earth?

Brent Kessel: (41:16)

I’d say for me, I have two tendencies. When thinking about the biggest issues the world faces, one is I’m inherently optimistic. I believe in human’s propensity towards goodness and love, even though there’s so many examples of exceptions to that, I think the, the long arc of history, the big arc of history is towards less violence and more, there’s just more and more and more people I find. And especially the younger generations. I mean, the people who are coming to work for Abacus today, who are in their twenties and thirties and, you know, even older, um, are, are so inspired they’re changing careers. They’re sometimes, they’re taking pay cuts and moving across the country to have this opportunity to, to work on big world problems and to, to solve things. Um, so I mean, I know we’ve had for decades, we’ve had the Peace Corps, we’ve had military service, we’ve had all kinds of ways of serving, um, being a teacher.

Brent Kessel: (42:22)

Um, but I, you know, and I know there’s a lot of, kind of bad, you know, flack that is given to younger people, you know, that they’re, they’re just addicted to their technology and they, they’re entitled and they don’t wanna do this and don’t wanna do that. And my experience isn’t, isn’t that like, sure, that’s a little bit of a hallmark of some, but there’s also a lot of heart and a lot of caring and a lot of, um, interconnectedness that I see, uh, with them. So inherent optimism I’d say is one reaction I have. And then the other reaction, which I’m not, uh, which I’m working to try and contain more, uh, as you know, Rob, is that I’m a doer. So, when I see a problem, I just, I kind of, I do like too much almost I, I go, you know, I go figure out who the people are on the leading edge of that problem.

Brent Kessel: (43:13)

And, and where’s the best research and who’s funding it most, you know, I impactfully and I try and catalyze, you know, investment in them or philanthropic funding for them, or, you know, lobbying my industry to include many more black and brown folks and women and LGBTQA folks in the financial advisory profession, so that we can then give good advice to those under served populations. And so, I’m so kind of caught in my doing, my overdoing, and my, my kind of excessive motivation in so many areas that I don’t really give myself time to pause and be overwhelmed, let’s say with, you know, a sense of powerlessness or a sense of, uh, inevitable decline. Um, and, and some might say, yeah, well, you’re in denial then, because it’s, it’s really bad and you’re just keeping yourself super busy so you don’t have to face how bad it is and, and maybe give yourself a sense of, of agency.

Brent Kessel: (44:17)

And, and I wouldn’t tell anyone that they’re wrong, if that was their view of me, um, it just, it is what I’ve tended to do. And so, I mean, my leading kind of growing edge at the moment is, is trying to do less and trying to give myself some more big windows of undistracted relaxation, where I can just kind of feel, feel the world, feel the people around me, feel the suffering, um, rather than just doing something to alleviate it. Um, so yeah, I mean, I mean, that’s my personal answer to it. And I certainly, I do have clients. I mean, I remember I was sitting with a client recently who’s very wealthy and who cares very deeply about the homeless problems in, in Southern California and had this vision of buying an old discarded cruise ship, which apparently you can pick up for very little money and getting the city to donate some dock space and like let’s house, a bunch of, you know, hundreds or thousands of homeless people on this cruise ship.

Brent Kessel: (45:20)

But it was just so daunting logistically that this person kind of said, oh, I, you know, I don’t feel like I can take this on alone at least. Um, so I do come in contact with folks who really want to do something, but don’t know where to start or, or who to partner with. Um, and I’d love to ask you, cuz I know in your, in your counseling practice that you deal with so many folks who, who have some resources and have amazing values and hearts, like what do you see as the, the edges that your clients are struggling with around making a difference in the world?

Robert Strock: (45:57)

Well, thanks for an answering that or for answering the question and also asking the question. Um, and I want to just clarify before, before I answer your question that, you know, it would be impossible to convey how much Brent is riveted toward helping the world. Like he’s saying, and it might almost sound like, whoa, you’re gonna just kick back and relax now after, after you’re doing all this, but I truly am rooting for what he’s saying, because he has been, uh, like a rocket ship going for, what can I do? How, how can I possibly improve the condition of the world at a point where it’s potentially at he’s own health’s risk. And, and so it is a question of balance always, and one size doesn’t fit all. And depending on who the person is, it’s a completely different response. It makes me think of something that we shared earlier and I may completely, uh, pardon the expression bastardize the, the quote, but it shows my bias slightly different than your bias, which was a David White poem, which is: are you ready?

Robert Strock: (47:08)

Are you ready to go for love, knowing for sure you’re gonna fail. Are you ready to go for love, knowing for sure you’re gonna fail. And I don’t know for sure I’m gonna fail, but I am concerned I’m gonna fail. I think you have done that without emphasizing or even believing the failure part. Uh, and I believe that’s a model, whether it’s small, medium, or large, that all of us could benefit for. Am I ready to go for my life? Knowing I may not succeed knowing, knowing I may fall flat on my face, knowing I might even blow the balance, but am I ready to go for it? Am I ready to keep asking those kind of questions? Um, and so. . .

Brent Kessel: (47:54)

Rob, if I could just jump in and throw, throw in real quick, there’s another David White quote that I love that so relates to what you just said, and what he says is: “The soul would rather fail at its own life than succeed at someone else’s.” And I love that, you know, like just go for it, go for your own soul’s vision of what life could be. And even if you fall on your face, that’s a better life and a better outcome than succeeding at someone else’s definition.

Robert Strock: (48:23)

Yeah, absolutely. And, and what that requires is an internal questioner, which is really, if we could instill one thing in the listener it’s to question, how do I optimize my life? And I am the authority, nobody else is the authority. I get to really move my life in the direction that I decide. And that doesn’t mean we’re omnipotent, it just means you, you can move your legs and your arms and your, and your mind in whatever way that is best possible for you. So I think that’s crucial, but to answer your other question, the emphasis for me is on quality of life. It’s always on quality of life. And so, because a good portion of my clients are wealthy and successful and are empty and they know they’re empty the emphasis on quality of life is it leads them to the absurd conclusion that I don’t even know how I’m gonna spend my money.

Robert Strock: (49:24)

I don’t even know how, I don’t wanna spoil my kids by leaving them too much money. And so, there are a number of people that haven’t given themselves the quality of life, and it’s like, they have a, it’s like a detached retina. They have this goal, you know, to reach a monetary goal, but it doesn’t have anything to do with life. It’s just, I’m gonna reach this goal. So, quality of life takes out the guilt trip. It, it really allows people to say, well, do I wanna give myself another house or do I want to give something to one of my kids or to all my kids or, or do I wanna consider the world? Do I wanna consider that it’s 2021, everyone gets to be the authority. But the key is, I hope is that people don’t suppress that we’re in 2021 and they also don’t feel pressure, but they do look at what would bring real quality of life, not, not a superficial quality of life, but a quality of life that my life is worth living for.

Robert Strock: (50:25)

So, that that’s really the key thing, and, and I really go outta my way to try not to have it be a guilt trip that’s doing it, and also not a grandiose trip that’s, that’s doing it either. Something that has to be grand versus whatever the potential is, wherever you find yourself, that, that there’s an optimistic suggestion that I can ask myself the question, how do I potentiate quality? It’s, at first, it’s my quality of life. And at some point it may go to quality of life. So it might, might transcend and include oneself and family, or it might always stay with my.

Brent Kessel: (51:08)

Right. So I actually have a question for you, and I love that you brought up the, the grandiose aspect of it, because when I, what I’ve been finding in myself as I’ve asked that question, cuz you’ve, you’ve planted that seed now for a couple of years with me is like, what, what does quality of life look like to me? I tend to be, um, such a future thinker. Um, you know, I’m a planner, it’s in my job title, Certified Financial Planner. Um, and so I’m always thinking about like, oh yeah, my quality of life would be amazing if I spent 28% of the time doing this and 40% of the doing that, and I, so what I would love to just genuinely ask you in this moment is like, for someone like me, who’s an organizer or a planner or someone who like runs an organization or is, you know, very kind of, uh, almost compulsively organized. What’s the, how do, how do we bite size that? How do you bite size? What is quality of life to me in this moment or on this day?

Robert Strock: (52:09)

Exactly. I think you partially answered the question in the way you ended, which is you move primarily in the day and secondarily in the planning and that, that, that you, that you really realize, you know what, I was never taught to recognize what quality of life means. I, I, is it pleasure? Is it a connection with someone else? Is it smiling at the, at the clerk at the store? Is, is it smiling when you walk by next to somebody? Um, is it saying hello to a homeless person, asking their name? What is quality of life genuinely for me? And I believe the answer is perpetually asking that question and having planning be second, not certainly relevant because that relates to the future, but not getting to a place where it replaces the next breath. Like how do I breathe in a way that actually feels good to me?

Robert Strock: (53:18)

How do I walk? How do I flex the muscle, so it actually feels good to the body. What’s my tone of voice. Like, you know, when I’m in my next conversation, you know what, what’s my thought-stream like, you know, how are my thoughts flowing or are they jagged all over the place? And can I be the one that can just have them flow in a way? Can I be the protector of my quality of life by asking the question? And how do I ask the question? Am I asking like, you know, well, how am I gonna get to my quality of life? Or, can you really see that the one that’s asking for quality of life is a quality of life. And that we, we can ask that question in a way that when we do it, it makes us smile, cuz we feel like we’re right there in the seat of our own authority, guiding ourselves. Not knowing, being confused, and a key part of it is valuing confusion and understanding that confusion is a sign of depth. Not staying confused necessarily, although sometimes it is, but if you ask a deeper question, you’re gonna get to not knowing you’re gonna get to confusion.

Robert Strock: (54:37)

So, it’s revering confusion and it’s asking the question, what is quality of life? And there is no shortcut because everybody’s answer is different. And so, the main common denominator is simply asking that question and enjoying the question. It can be a, a punishment to ask that question or it can be a liberation even without answers because you know, you care about quality of life or your quality of life. And to me, that’s an e-ticket to Disneyland in the real world.

Brent Kessel: (55:12)

Yeah. It also, I’m just reflecting as you were speaking on, uh, I find myself, you know, I think like everybody, so many times in a week, in a conversation, or even just in my own inbox with something that is, is, isn’t quality, you know, is dragging me down. And certainly if it’s a conversation, or someone else, you know, needing something, and I’m like this, this isn’t really how I want to be spending my time, I’m not just gonna be like, uh, you know, see I’m out. But I think, I think at a minimum being aware like, oh, this is kind of a, this is crossing a boundary where I’m not actually caring about my quality of life in this moment. So you can make a different, I can make a different choice next time. And then in some situations, being able to actually set that boundary and, you know, end the conversation in five minutes instead of 45 minutes. Um, I love what you’re saying about, you know, the tremendous challenge, and self-honoring that’s required to ask the question and then to allow, to know, that that’s probably gonna lead to some internal discomfort and probably external, like letting other people down that, that FOCO thing I mentioned earlier, like other people aren’t necessarily prioritizing your quality of life. They want whatever they want in the moment.

Robert Strock: (56:34)

Yeah. Yeah, and and I think for you, interestingly, and you again had the answer in your conversation, you are at a place now where you get to boundary, you get to boundary your quality of life. You get to wake up that protector and you really, there is no reason for you to cave on quality of life, especially because the quality of life for you is not dominantly self-centered, it’s, it’s, it is self-centered in the sense that it’s gonna hit your sweet-spots, but it’s a positive self-centered. So, my overwhelming wish is because you have 98 opportunities and organizations and people to do good, and only you know, the 10–you know, narrowing it down to your top 10–so you’re only exactly the kind of busy you want to be. And you have brought your life to such a state of, uh, multiple, multiple opportunities that you get to really boundary it.

Robert Strock: (57:48)

You get to, but it will require you giving up some pleasing of others. It will require some disappointing others. It will require some judgements and it will even require some self-doubt, am I just being selfish? And the discernment between selfish and self-caring and the self is blurry because the self includes others for many people. And so self-centered oftentimes gets a bad because ultimately to be self-directed and to find a place that really wants to be your maximum caring is, is our potential is our responsibility in the best sense of responsibility. And, especially, I would say for you, you know, you boundering things, which, you know, we don’t have time to go into all the details I know you’re doing, but I know you’re, you’re really a start of the ball there. And I just trust that so much that you will find once you give yourself more and more permission to boundary that that is something that is going to be more and more liberating and allow your heart to just be more and more filled.

Robert Strock: (59:04)

And as I say that to you, I wanna really be clear to everyone that’s listening, that the answer and the guidance for others might be persevere, be more disciplined, create more opportunities, overlap with people that you care about. That, that there is no one answer. There is one question. So, the answer is the question, and the question is how do I maximize my potential of balancing my caring for myself, those that are dear to my heart and the rest of the world, and how do I do that? Recognizing as 2021, recognizing my unique situation, honoring my unique situation, not comparing myself with others. How do I do that?

Brent Kessel: (59:50)

I’d love to just, uh, double-click on that by saying, I think asking ourselves really honest questions about, you know, the, when I make a choice for my own pleasure, let’s say, um, and, and, oh my God buying, you know, I remember back in 2012 when I had been on the list for one of the first Teslas for a couple of years, and I was like, this car is gonna just make my life amazing. And I’m gonna look, you know, so sophisticated pulling up to some event in it and it I’m gonna get this done and that done. And you know, it, it, anyway, I sold it hard to myself and then, you know, being really honest afterwards, like, yeah, it, it was amazing, and it had that new car smell for a while, but about the time the new car smell wore off

Brent Kessel: (01:00:39)

so did all of those incredible, you know, like it’s gonna change my life attributes. And that’s not to say that like, then I should never buy anything for pleasure again, or I should never think that luxury is enjoyable. There’s, you know, lots of luxuries and pleasures that are enjoyable, um, and including very small ones, and there’s lots of free things that are incredibly enjoyable. And there’ve been charitable things, you know, and, and generosities that I thought would really touch my heart that ended up just not touching my heart. Um, and I think for us, I think one of the things we haven’t been taught to do, like you said, we’ve never really been taught to ask what is quality of life for me, we mostly take our cues from culture and advertising. Um, but we also, haven’t been taught to kind of Monday morning quarterback our decisions and say, how did that actually go? You know, did I feel fulfilled by that? Um, did it improve my quality of life and for how long? And, um, I think doing that and just being super honest with ourselves and journaling about it, or talking to a really close, trusted, loved one about it with as much honesty as possible can, can support that turning of the super tanker wheel for the next decision.

Robert Strock: (01:02:00)

You know, you, you said, I think four times what I wanted to say to you earlier, and I hope the listener hears this loud and clear, but your honesty about what touches you, your awareness and your honesty about what touches you and what doesn’t touch you is itself the revelation of quality of life. And so, it does require questioning, it requires awareness, and it requires honesty and trueness to your deepest sense of self. And I think that that’s a great place for us to really wind this down and I so appreciate the fact that you have so many areas where you’ve succeeded. And one of the ones that hasn’t been sacrificed is that inquiring, is that honesty, you know, is enough humility to realize I haven’t arrived now from my vantage point for people have watched, nobody ever arrives, but to keep questioning and to have that honesty is something that we’re all capable of. And I know Brent you’ll join me in being that just a deep prayer and wish for everyone that’s listening and obviously way beyond everyone that’s listening.

Brent Kessel: (01:03:25)

Absolutely. And love that you’re putting so much heart and soul and resources into this project of The Missing Conversation, and I hope it really helps a lot of people.

Robert Strock: (01:03:37)

Thank you. And I’m gonna hold you to your giving us the list of, uh, places that people can look, look at and investigate for themselves if they, if they feel inclined, because I know you, you have those resources and, and thank you all for your attention to everything. And as I’ve said in various episodes and hopefully your retention as well. So, that’s my prayer. Thanks so much. Thank you, Brent.

Brent Kessel: (01:04:04)

Thank you.

Join The Conversation

Join The Conversation

If The Missing Conversation sounds like a podcast that would be inspiring to you and touches key elements of your heart, please click subscribe and begin listening to our show. If you love the podcast, the best way to help spread the word is to rate and review the show. This helps other listeners, like you, find this podcast. We’re deeply grateful you’re here and that we have found each other. Our wish is that this is just the beginning.

We invite you to learn more about The Global Bridge Foundation—an organization collaborating to heal communities and the world at TheGlobalBridge.org.

Visit our podcast archive page